Recently I came across the Dutch Wikipedia page for privacy. It mentions that one of the major dictionaries states that the word privacy appeared in the Dutch language after 1950. However, the Dutch National Library archives show that privacy can be traced back to at least 1884 as a foreign term. It's used on its own in the Dutch language since at least 1912. Let's take a walk through privacy history in Dutch newspapers.

Warren and Brandeis' 1890 paper titled The right to privacy is probably the oldest well-known historical publication on privacy. This publication is considered the first legally oriented definition of privacy and came to be in a time of technological developments. The word privacy itself is quite a bit older though, and may be a British invention. In the British Newspaper Archive we can find its first appearance in 1721, though older records do exist.

First appearances in Dutch newspapers

Privacy first entered the Dutch vocabulary as a foreign, descriptive characteristic of the British. As can be seen in an 1884 article about London pawnshops. According to the newspaper, the interior of the pawnshops was noteworthy. Not only was there a public service desk, but also segregated booths with high sides that provided privacy to the person doing business. The newspaper described this as an expression of "the covertness (privacy) that encompasses the entirety of English life."

It is thus no coincidence that the word first primarily appears in quotes. In fact, the first Dutch reference to privacy I could find dates back to 1879 and quotes the Royal family about a marriage they want to perform "in all privacy." That the article suggests that it may actually be one of the most lavish and public weddings yet is something we'll conveniently ignore for now.

Then, an 1891 serial print of a book called The Life in South Africa recites two lines from an 1808 poem by Sir Walter Scott: Woe to the vassal, who durst pry / Into Lord Marmions privacy!

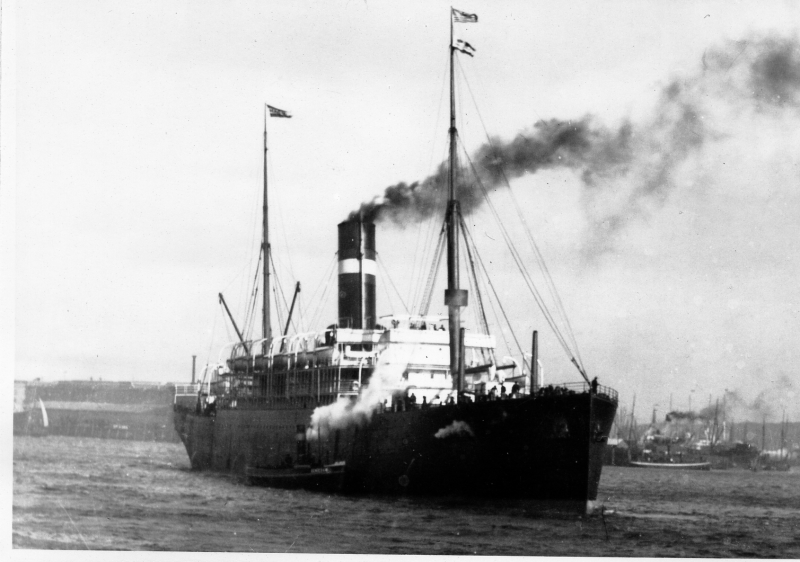

The next mention of privacy concerns the latest steamship of the Holland America Line: Rotterdam. At the time, the ship was the largest Dutch ship in its class with room for 1161 passengers. Rotterdam left for her maiden voyage across the Atlantic Ocean on 18 August 1897. The ship was a noteworthy arrival in New York, with multiple newspapers commenting on the new ship cited as foreign news in a Dutch newspaper. The New York Evening Telegraph mentions the interior design, which had developed away from steerage and now offered cabins to all passengers. This was a positive development for both privacy and general decency. Steerage was the lowest class of passenger accommodations, with 200 to 400 people in a single large space. They would sleep bunked and getting food that is not served, but as a 1906 book describes "doled out with less courtesy than one would find in a charity soup kitchen. [...] Every cabin passenger who has seen and smelt the steerage from afar, knows that it is often indecent and inhuman [...] and cruel besides." Privacy was not a thing in steerage and the new class of passenger ships offered improvement.

First uses in Dutch language

In 1911, a Dutch journalist visited the 'Curative Institute', situated in the heart of London at 32 St. James' Street. The Institute was founded and headed by Eugen Sandow, who was a celebrity at the time and is nowadays best known as the father of bodybuilding. He employed physicians and physical trainers at the institute, initially aimed at offering people an improved physique. The building was so designed, that each visitor went through a private dressing room to a private exercise room. As a result, a visitor would notice little else from others except for some muffled sound and was able to exercise in private. The journalist even proclaims the Dutch could learn much from the British about "privacy". Still in quotes here.

Then, in 1912, we find the first use of privacy as a concept of its own in Dutch. De Nieuwe Courant published a summary of the Fifth Accountants day of the Dutch Accountants Association. Central theme are the legal guidelines about the publication of annual accounts of limited companies (Naamloze Venootschappen in Dutch). The privacy of the limited company was weighted against the needs of shareholders. Publication of annual accounts would be necessary when shareholders were not feasibly reached individually, unless there were reasons to protect the privacy of the business. No quotation marks, italicising or any marking of a foreign word. Just privacy used in a Dutch sentence and a Dutch context, all the way back in 1912.

Comparisons to other cultures

In the following decades, privacy is most often used in Dutch newspapers when comparing cultures. Like a 1913 letter discussing pensions in the U.S., which compares the housing interior to pensions in Berlin. Rooms are connected with double doors, which need additional soundproofing to prevent disturbances and unwanted sounds. In pensions with diverse, international visitors "privacy" was preferred more than elsewhere. Or a 1923 article about how little privacy is provided to passengers of train compartments, contrasted to those in Europe.

Algemeen Handelsblad wrote of living in New York in 1925, where standard 2-bedroom housing is described as having thin walls. Hearing the gramophones and radios from other people in the building hampered the feeling of seclusion one would desire in one's own homestead. A 1927 opinion piece states that "the American is simply much less fond of "privacy" than the European." Not all is in comparison with the US though. A 1928 travel journal describes a stay in Havana, at a hotel with half doors separating the bedrooms from the hallway. Here, it states, a shy European may desire trans-atlantic "privacy".

The newspaper Het Vaderland published an excerpt from a 1928 book by professor Ernst Cohen, who spent several months as a non-resident professor in the United States. The book primarily deals with the organisation of scientific research overseas, but it also includes descriptions of American home life. One passage states that Americans seem to care little for their "privacy", a view that is shared by the English as well. Bedrooms are described as having doors, but they are always open during the day. There are no separations between gardens and neighbours walk over each other's land. Also noteworthy from a cultural perspective is the remark Americans make unannounced house calls during day and evening.

A 1928 article about Dutch housing developments, reprinted from foreign press, gives an outside perspective on Dutch privacy norms. The article mentions that in newly developed neighbourhoods, great care was taken to preserve privacy. An innovative system of pulleys attached to the front of the building allowed for heavy furniture to be lifted to the upper floors. As a result, there was no need for broad, communal staircases. Every flat got their own staircase, allowing more privacy for the people who live there.

Following history

As we continue, the newspapers roughly follow the more well-known history of privacy. The number of newspaper articles mentioning privacy grows tenfold in this time, so I limit myself to just a few links.

The 1930s were a tumultuous time when considered through the lens of privacy. In 1933, Hindenburg signed a decree that placed Germany under absolute dictatorship. Ahead of World War 2, Germany rescinds all guarantees of personal liberty, among them the privacy of communication. In 1935, privacy concerns are raised against the first portable radio phones, which would disturb the quietness of public places.

In 1936, Charlie Chaplin got married to Paulette Godard. Following their return, Chaplin would refuse to disclose any information, stating that "one must have privacy about some things." Following a long list of tabloid journalism scandals, the U.K. has a public discussion about the limits on press freedom and respecting the privacy of individuals. The Nieuwe Haarlemsche courant (1937) offers background on this issue, stating that the subject is relevant for The Netherlands as well.

It's here that I stop my investigation. During WW2, the Dutch did not have free press and articles are often preceded by a warning that they are based on the national socialist propaganda. Then after WW2 it's more of the same, with privacy still used as a foreign word in quotation marks. It's in the 1950s that the word starts to be used more frequently on its own. Hopefully you found this short trip through history as interesting as I did.